React có thể chậm. Ý tôi là, bất kỳ ứng dụng React với kích thước trung bình có thể có vẻ chậm. Nhưng trước khi bạn bắt đầu tìm kiếm các phương án thay thế, bạn nên biết rằng bất kỳ ứng dụng Angular hay Ember cỡ trung bình nào cũng chậm.

Tin vui là: Nếu bạn quan tâm đến hiệu suất, nó khá dễ dàng để làm bất kỳ ứng dụng React trở nên siêu nhanh ⚡.️ Đây là cách.

Measuring React Performance

What do I mean by “slow”? Let’s take an example:

I’m working on an open-source project called admin-on-rest, which leverages material-ui and Redux to provide an admin GUI for any REST API. This application has a datagrid page, displaying a list of records in a table. When the user changes the sort order, or goes to the next page, or filters the result, the interface isn’t as responsive as I would expect.

The following screencast shows the refresh slowed down five times:

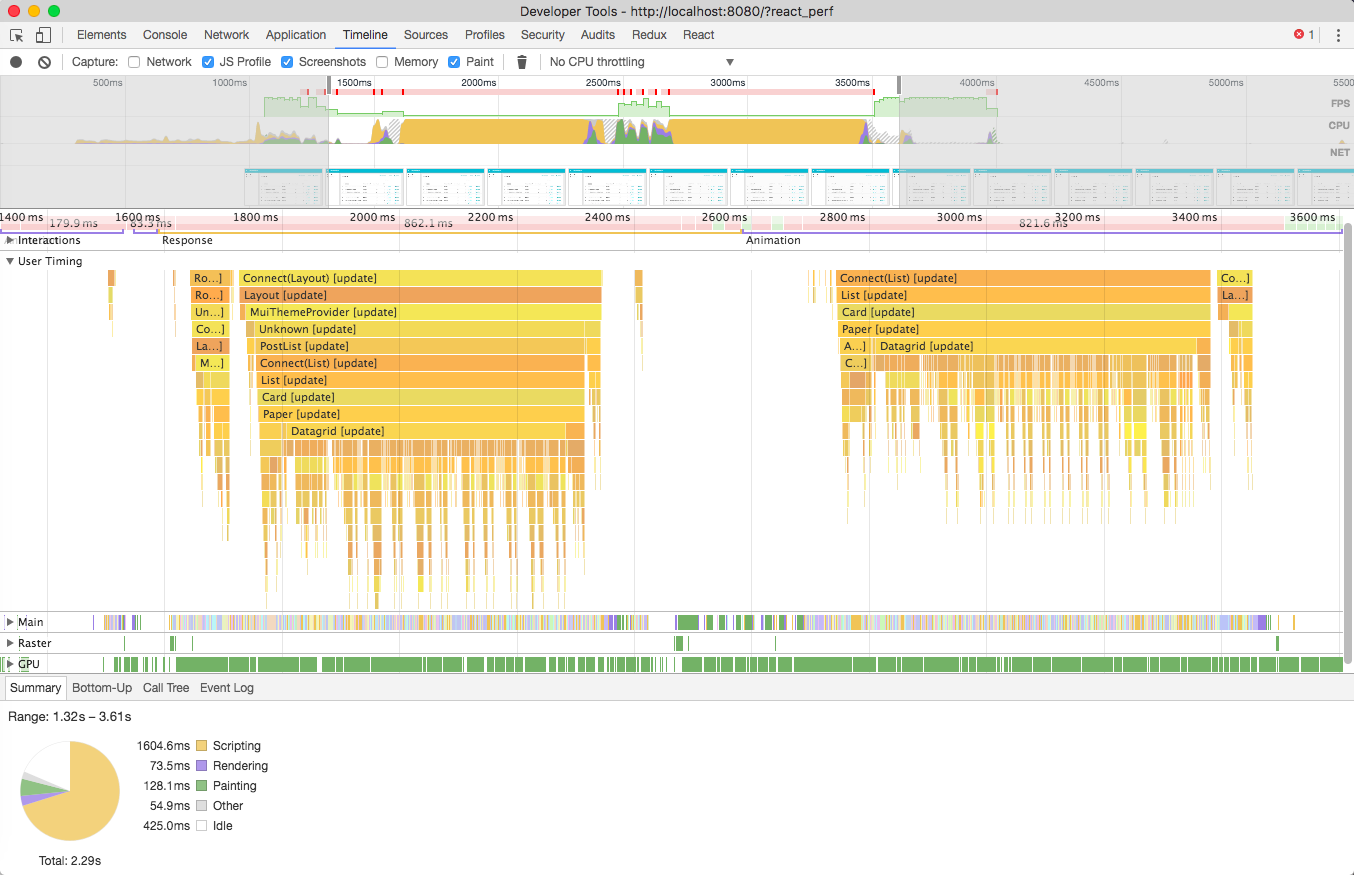

To see what’s happening, I append a ?react_perf to the URL. This enables Component Profiling since React 15.4. I wait for the initial datagrid to load. Then I open the Chrome Developer Tools on the Timeline tab, hit the “Record” button, and click on a table header to update the sort order.

Once the data refreshes, I hit the “Record” button again to stop recording, and Chrome displays a yellow flamegraph with a “User Timing” label.

If you’ve never seen a flamegraph, it can look intimidating, but it’s actually very easy to use. This “User Timing” graph shows the time passed in each of your components. It hides the time spend inside React internals (you can’t optimize this time anyway), so it lets you focus on optimizing your app.

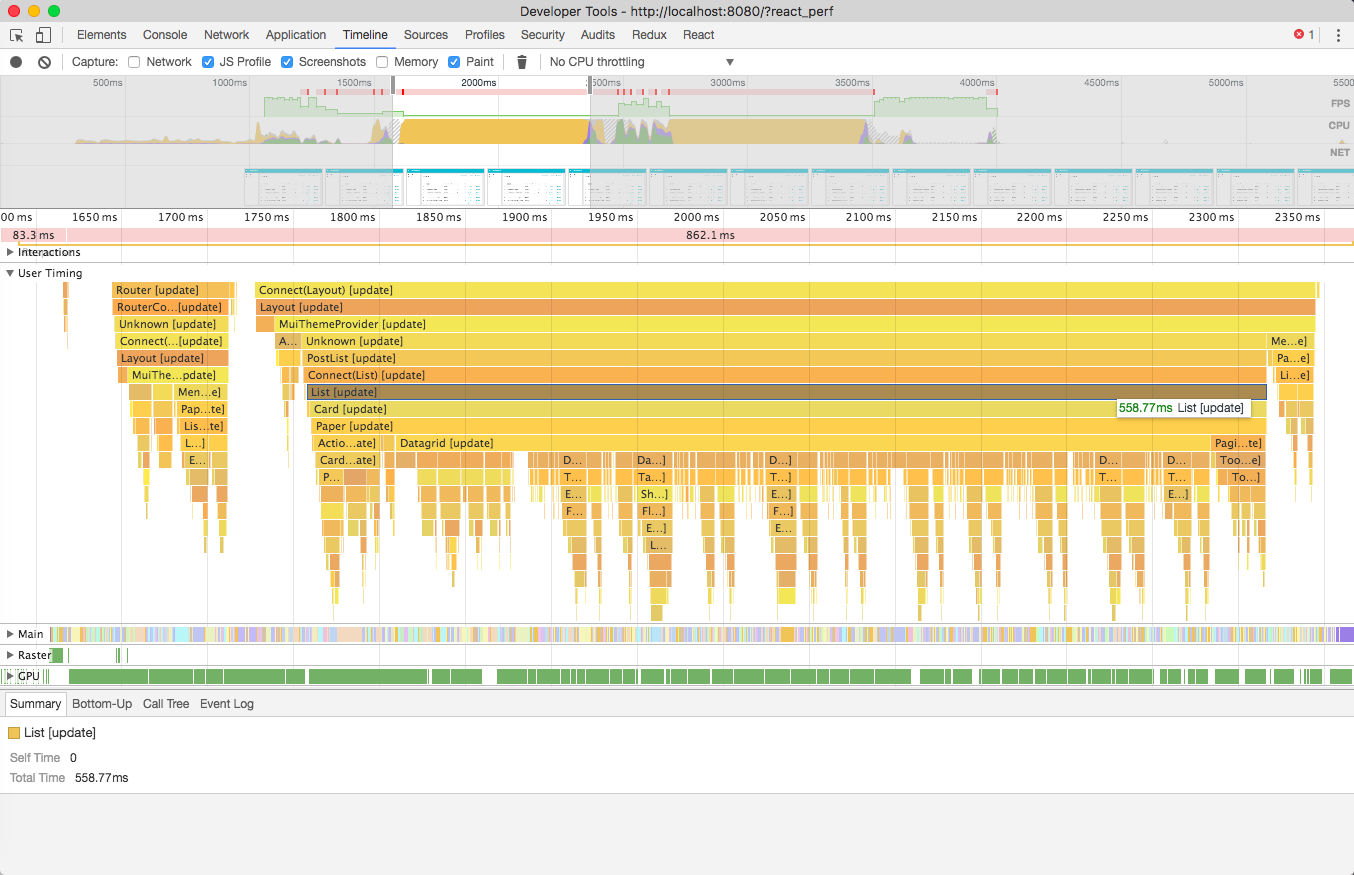

The Timeline displays screenshots of the window at various stages, this lets me zoom in to the moment I clicked on the table header:

It seems that my app rerenders the <List> component just after clicking on the sort button, before even fetching the REST data. And this takes more than 500ms. The app just updates the sort icon in the table header, and displays a grey overlay on the datagrid to show that the data is being fetched.

To put it otherwise, the app takes half a second to provide visual feedback to a click. Half a second is definitely perceivable — UI experts say that users perceive an interface change as instantaneous when it’s below 100ms. A change slower than that is what I mean by “slow”.

Why Did You Update?

In the flamegraph above, you can see many tiny pits. That’s not a good sign. It means that many components are rerendered. The flamegraph shows that the <Datagrid> update takes the most time. Why did the app rerender the entire datagrid before fetching new data? Let’s dig down.

Understanding the causes of a rerender often implies adding console.log() statements in render() functions. For functional components, you can use the following one-liner Higher-Order Component (HOC):

// in src/log.js

const log = BaseComponent => props => {

console.log(`Rendering ${BaseComponent.name}`);

return <BaseComponent {…props} />;

}

export default log;// in src/MyComponent.js

import log from ‘./log’;

export default log(MyComponent);Tip: Another React performance tool worth mentioning is why-did-you-update. This npm package patches React to emit console warnings whenever a component rerenders with identical props. Caveats: The output is verbose, and it doesn’t work on functional components.

In the example, when the user clicks on a header column, the app emits an action, which changes the state: the list sort order (currentSort) is updated. This state change triggers the rerendering of the <List> page, which in turn rerenders the entire <Datagrid> component. We want the datagrid header to be immediately rendered to show the sort icon change as a feedback to user action.

What makes a React app slow is usually not a single slow component (that would translate in the flamegraph as one large pit). What makes a React app slow is, most of the time, useless rerenders of many components.

You may have read that the React VirtualDom is super fast. That’s true, but in a medium size app, a full redraw can easily render hundreds of components. Even the fastest VirtualDom templating engine can’t make that in less than 16ms.

Cutting Components To Optimize Them

Here is the <Datagrid> component render() method:

// in Datagrid.js

render() {

const {

resource,

children,

ids,

data,

currentSort

} = this.props;

return (

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

{Children.map(children, (field, index) =>

<DatagridHeaderCell

key={index}

field={field}

currentSort={currentSort}

updateSort={this.updateSort}

/>

)}

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

{ids.map(id => (

<tr key={id}>

{Children.map(children, (field, index) =>

<DatagridCell

record={data[id]}

key={`${id}-${index}`}

field={field}

resource={resource}

/>

)}

</tr>

))}

</tbody>

</table>

);

}This seems like a very simple implementation of a datagrid, yet it is very inefficient. Each <DatagridCell> call renders at least two or three components. As you can see in the initial interface screencast, the list has 7 columns, 11 rows, that means 7113 = 231 components rerended. When only the currentSort changes, it’s a waste of time. Even though React doesn’t update the real DOM if the rerendered VirtualDom is unchanged, it takes about 500ms to process all the components.

In order to avoid a useless rendering of the table body, I must first extract it:

// in Datagrid.js

render() {

const {

resource,

children,

ids,

data,

currentSort

} = this.props;

return (

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

{React.Children.map(children, (field, index) =>

<DatagridHeaderCell

key={index}

field={field}

currentSort={currentSort}

updateSort={this.updateSort}

/>

)}

</tr>

</thead>

<DatagridBody resource={resource} ids={ids} data={data}>

{children}

</DatagridBody>

</table>

);

);

}I created a new <DatagridBody> component by extracting the table body logic:

// in DatagridBody.js

import React, { Children } from 'react';

const DatagridBody = ({ resource, ids, data, children }) => (

<tbody>

{ids.map((id) => (

<tr key={id}>

{Children.map(children, (field, index) => (

<DatagridCell

record={data[id]}

key={`${id}-${index}`}

field={field}

resource={resource}

/>

))}

</tr>

))}

</tbody>

);

export default DatagridBody;Extracting the table body has no effect on performance, but it reveals the path to optimization. Large, general purpose components are hard to optimize. Small, single-responsibility components are much easier to deal with.

shouldComponentUpdate

The React documentation is very clear about the way to avoid useless rerenders: shouldComponentUpdate(). By default, React always renders a component to the virtual DOM. In other terms, it’s your job as a developer to check that the props of a component didn’t change and skip rendering altogether in that case.

In the case of the <DatagridBody> component above, there should be no rerender of the body unless the props have changed.

So the component should be completed as follows:

import React, { Children, Component } from 'react';

class DatagridBody extends Component {

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps) {

return (

nextProps.ids !== this.props.ids || nextProps.data !== this.props.data

);

}

render() {

const { resource, ids, data, children } = this.props;

return (

<tbody>

{ids.map((id) => (

<tr key={id}>

{Children.map(children, (field, index) => (

<DatagridCell

record={data[id]}

key={`${id}-${index}`}

field={field}

resource={resource}

/>

))}

</tr>

))}

</tbody>

);

}

}

export default DatagridBody;Tip: As an alternative to implementing

shouldComponentUpdate()manually, I could inherit from React’sPureComponentinstead ofComponent. This would compare all props using strict equality (===) and rerender only if any of the props change. But I know thatresourceandchildrencannot change in that context, so I don’t need to check for their equality.

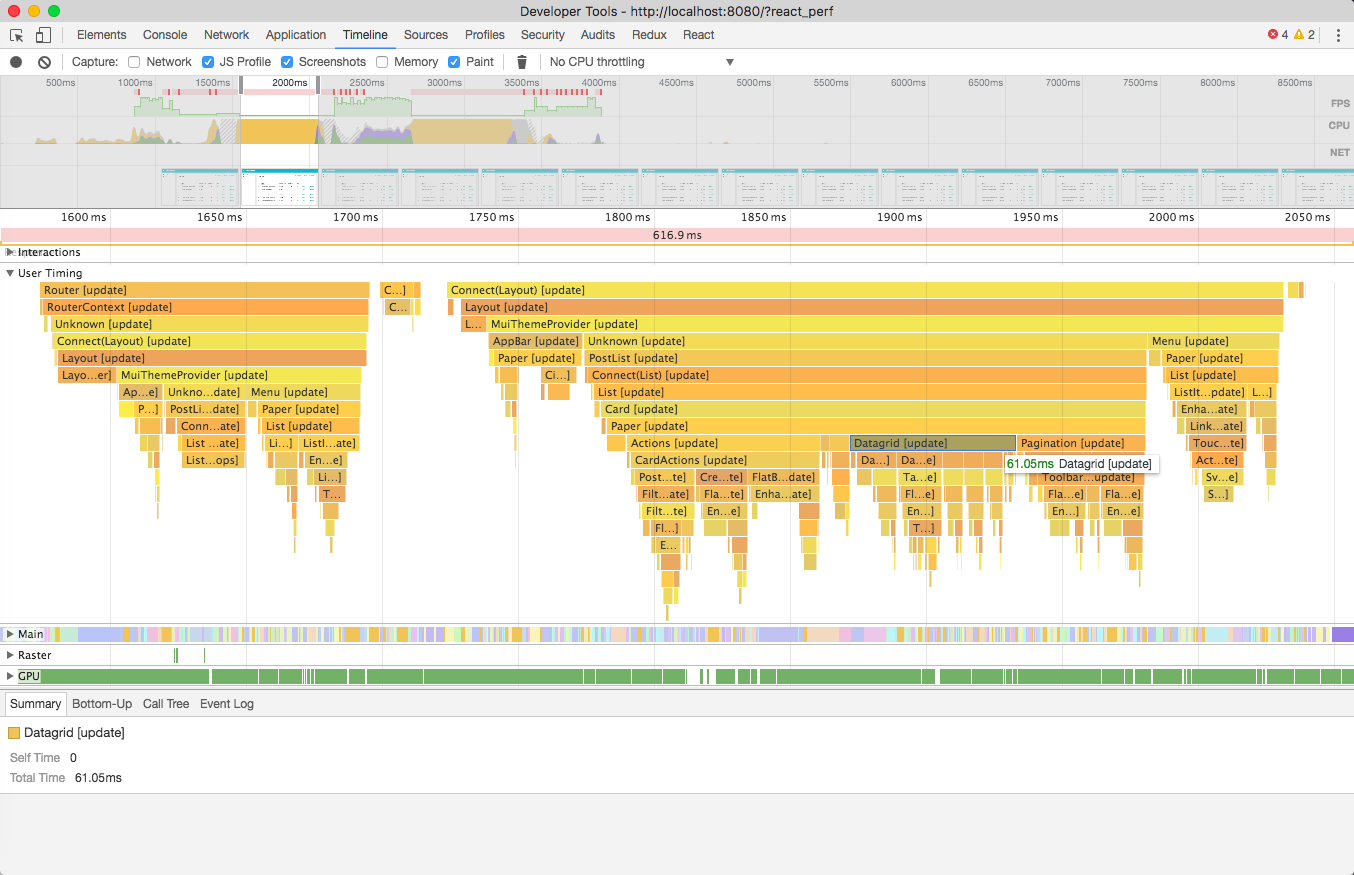

With this optimization, the rerendering of the <Datagrid> component after clicking on a table header skips the table body and its 231 components entirely. This reduces the update time from 500ms to 60ms. That’s a net performance improvement of more than 400ms!

Tip: Don’t get fooled by the flamegraph width, it’s zoomed even more than the previous flamegraph. This one is definitely better!

The shouldComponentUpdate optimization has removed a lot of pits in the graph, and reduced the overall rendering time. I can use the same trick to avoid even more rerenders (e.g. to avoid rendering the sidebar, the action buttons, the table headers that didn’t change, the pagination). After about an hour of work, the entire page renders just 100ms after clicking on a header column. That’s fast enough — even if there is still room for optimization.

Adding a shouldComponentUpdate method may seem cumbersome, but if you care about performance, most of the components you write should end up with one.

Don’t do it everywhere — executing shouldComponentUpdate on simple components is sometimes slower than just rendering the component. Don’t do that too early in the life of an application either — this would be premature optimization. But as your apps grow, and you can detect performance bottlenecks in your components, add shouldComponentUpdate logic to remain fast.

Recompose

I’m not very happy with the previous change on <DatagridBody>: because of shouldComponentUpdate, I had to transform a simple, functional component to a class-based component. This adds more lines of code, and every line of code has a cost — to write, to debug, and to maintain.

Fortunately, you can implement the shouldComponentUpdate logic in a higher-order component (HOC) thanks to recompose. It’s a functional utility belt for React, providing for instance the pure() HOC:

// in DatagridBody.js

import React, { Children } from 'react';

import pure from 'recompose/pure';

const DatagridBody = ({ resource, ids, data, children }) => (

<tbody>

{ids.map((id) => (

<tr key={id}>

{Children.map(children, (field, index) => (

<DatagridCell

record={data[id]}

key={`${id}-${index}`}

field={field}

resource={resource}

/>

))}

</tr>

))}

</tbody>

);

export default pure(DatagridBody);The only difference between this code and the initial implementation is the last line: I export pure(DatagridBody) instead of DatagridBody. pure is like PureComponent, but without the extra class boilerplate.

I can even be more specific and target only the props that I know may change, using recompose’s shouldUpdate() instead of pure():

// in DatagridBody.js

import React, { Children } from 'react';

import shouldUpdate from ‘recompose/shouldUpdate’;

const DatagridBody = ({ resource, ids, data, children }) => (

...

);

const checkPropsChange = (props, nextProps) =>

(nextProps.ids !== props.ids ||

nextProps.data !== props.data);

export default shouldUpdate(checkPropsChange)(DatagridBody);The checkPropsChange function is pure, and I can even export it for unit tests.

The recompose library offers more performance HOCs, like onlyUpdateForKeys(), which does exactly the type of check I did in my own checkPropsChange:

// in DatagridBody.js

import React, { Children } from 'react';

import onlyUpdateForKeys from ‘recompose/onlyUpdateForKeys’;

const DatagridBody = ({ resource, ids, data, children }) => (

...

);

export default onlyUpdateForKeys([‘ids’, ‘data’])(DatagridBody);I warmly recommend recompose. Beyond performance optimization, it helps you extract data fetching logic, HOC composition, and props manipulation in a functional and testable way.

Redux

If you’re using Redux to manage application state (which I also recommend), then connected components are already pure. No need to add another HOC.

Just remember that if only one of the props change, then the connected component rerenders — this includes all its children, too. So even if you use Redux for page components, you should use pure() or shouldUpdate() for components further down in the render tree.

Also, beware that Redux does the props comparison using strict equality. Since Redux connects the state to a component’s props, if you mutate an object in the state, Redux props comparison will miss it. That’s why you must use immutability in your reducers.

For instance, in admin-on-rest, clicking on a table header dispatches a SET_SORT action. The reducer listening to that action must pay attention to replace objects in the state, not update them:

// in listReducer.js

export const SORT_ASC = 'ASC';

export const SORT_DESC = 'DESC';

const initialState = {

sort: 'id',

order: SORT_DESC,

page: 1,

perPage: 25,

filter: {},

};

export default (previousState = initialState, { type, payload }) => {

switch (type) {

case SET_SORT:

if (payload === previousState.sort) {

// inverse sort order

return {

...previousState,

order: oppositeOrder(previousState.order),

page: 1,

};

}

// replace sort field_

return {

...previousState,

sort: payload,

order: SORT_ASC,

page: 1,

};

// ...

default:

return previousState;

}

};With this reducer, when Redux checks for changes using triple equal, it finds that the state object is different, and rerenders the datagrid. But had we mutated the state, Redux would have missed the state change, and skipped rerendering by mistake:

// don't do this at home

export default (previousState = initialState, { type, payload }) => {

switch (type) {

case SET_SORT:

if (payload === previousState.sort) {

// never do this

previousState.order = oppositeOrder(previousState.order);

return previousState;

}

// never do that either

previousState.sort = payload;

previousState.order = SORT_ASC;

previousState.page = 1;

return previousState;

// ...

default:

return previousState;

}

};To write immutable reducers, other developers like to use immutable.js, also from Facebook. I find it unnecessary, since ES6 destructuring makes it easy to selectively replace a component properties. Besides, Immutable is heavy (60kB), so think twice before you add it to your project dependencies.

Reselect

To prevent useless renders in (Redux) connected components, you must also make sure that the mapStateToProps function doesn’t return new objects each time it is called.

Take for instance the <List> component in admin-on-rest. It grabs the list of records for the current resource (e.g. posts, comments, etc) from the state using the following code:

// in List.js

import React from 'react';

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

const List = (props) => ...

const mapStateToProps = (state, props) => {

const resourceState = state.admin[props.resource];

return {

ids: resourceState.list.ids,

data: Object.keys(resourceState.data)

.filter(id => resourceState.list.ids.includes(id))

.map(id => resourceState.data[id])

.reduce((data, record) => {

data[record.id] = record;

return data;

}, {}),

};

};

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(List);The state contains an array of all the previously fetched records, indexed by resource. For instance, state.admin.posts.data contains the list of posts:

{

23: { id: 23, title: “Hello, World”, /* … */ },

45: { id: 45, title: “Lorem Ipsum”, /* … */ },

67: { id: 67, title: “Sic dolor amet”, /* … */ },

}The mapStateToProps function filters this state object to return only the records actually displayed in the list. Something like:

{

23: { id: 23, title: “Hello, World”, /* … */ },

67: { id: 67, title: “Sic dolor amet”, /* … */ },

}The problem is that each time mapStateToProps runs, it returns a new object, even if the underlying objects didn’t change. As a consequence, the <List> component rerenders every time something in the state changes — while id should only change if the date or ids change.

Reselect solves this problem by using memoization. Instead of computing the props directly in mapStateToProps, you use a selector from reselect, which returns the same output if the input didn’t change.

import React from 'react';

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

import { createSelector } from 'reselect'

const List = (props) => ...

const idsSelector = (state, props) =>

state.admin[props.resource].ids

const dataSelector = (state, props) =>

state.admin[props.resource].data

const filteredDataSelector = createSelector(

idsSelector,

dataSelector

(ids, data) => Object.keys(data)

.filter(id => ids.includes(id))

.map(id => data[id])

.reduce((data, record) => {

data[record.id] = record;

return data;

}, {})

)

const mapStateToProps = (state, props) => {

const resourceState = state.admin[props.resource];

return {

ids: idsSelector(state, props),

data: filteredDataSelector(state, props),

};

};

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(List);Now the <List> component will only rerender if a subset of the state changes.

As for recompose, reselect selectors are pure functions, easy to test and compose. It’s a great way to code your selectors for Redux connected components.

Beware of Object Literals in JSX

Once your components become more “pure”, you start detecting bad patterns that lead to useless rerenders. The most common is the usage of object literals in JSX, which I like to call “The infamous \{\{”. Let me give you an example:

import React from 'react';

import MyTableComponent from './MyTableComponent';

const Datagrid = (props) => (

<MyTableComponent style={{ marginTop: 10 }}>...</MyTableComponent>

);The style prop of the <MyTableComponent> component gets a new value every time the <Datagrid> component is rendered. So even if <MyTableComponent> is pure, it will be rendered every time <Datagrid> is rendered. In fact, each time you pass an object literal as prop to a child component, you break purity. The solution is simple:

import React from 'react';

import MyTableComponent from './MyTableComponent';

const tableStyle = { marginTop: 10 };

const Datagrid = (props) => (

<MyTableComponent style={tableStyle}>...</MyTableComponent>

);This looks very basic, but I’ve seen this mistake so many times that I’ve developed a sense for detecting the infamous \{\{ in JSX. I routinely replace it with constants.

Another usual suspect for hijacking pure components is React.cloneElement(). If you pass a prop by value as second parameter, the cloned element will receive new props at every render.

// bad

const MyComponent = (props) => <div>{React.cloneElement(Foo, { bar: 1 })}</div>;

// good

const additionalProps = { bar: 1 };

const MyComponent = (props) => (

<div>{React.cloneElement(Foo, additionalProps)}</div>

);This has bitten me a couple times with material-ui, for instance with the following code:

import { CardActions } from 'material-ui/Card';

import { CreateButton, RefreshButton } from 'admin-on-rest';

const Toolbar = ({ basePath, refresh }) => (

<CardActions>

<CreateButton basePath={basePath} />

<RefreshButton refresh={refresh} />

</CardActions>

);

export default Toolbar;Although <CreateButton> is pure, it was rendered every time <Toolbar> was rendered. That’s because material-ui’s <CardActions> adds a special style to its first child to accommodate for margins — and it does so with an object literal. So <CreateButton> received a different style prop every time. I solved it using recompose’s onlyUpdateForKeys() HOC.

// in Toolbar.js

import onlyUpdateForKeys from 'recompose/onlyUpdateForKeys';

const Toolbar = ({ basePath, refresh }) => (

...

);

export default onlyUpdateForKeys(['basePath', 'refresh'])(Toolbar);Conclusion

There are many other things you should do to keep your React app fast (using keys, lazy loading heavy routes, the react-addons-perf package, using ServiceWorkers to cache app state, going isomorphic, etc), but implementing shouldComponentUpdate correctly is the first step — and the most rewarding.

React isn’t fast by default, but it offers all the tools to be fast whatever the size of the application.

This may seem counterintuitive, especially since many frameworks offering an alternative to React claim themselves as n times faster. But React puts developer experience before performance. That’s the reason why developing large apps with React is such a pleasant experience, without bad surprises, and a constant implementation rate.

Just remember to profile your app every once in a while, and dedicate some time to add a few pure() calls where it’s needed. Don’t do it first, or spend too much time to over optimize each and every component — except if you’re on mobile. And remember to test on various devices to get a good impression of your app’s responsiveness from a user’s point of view.

If you want to read more about React performance optimization, here is a list of great articles on the subject:

- React Rally: Animated — React Performance Toolbox: A fabulous slide deck by Christopher Chedeau (Vjeux), one of the React Native developers. He’s French, by the way.

- Progressive Web Apps with React.js: Part 2 — Page Load Performance by Addy Osmany, who works at Google and writes a lot of blog posts about web performance

- Optimizing the Performance of Your React Application focuses on the

react-addons-perfpackage to profile React apps precisely - React Higher Order Components in depth, interesting for the introduction of Render Hijacking

- A Deep Dive into React Perf Debugging describes a step-by-step debugging session with Chrome dev Tools

- Making React reactive: the pursuit of high performing, easily maintainable React apps on using Observables to avoid rerenders

Source: http://marmelab.com/blog/2017/02/06/react-is-slow-react-is-fast.html