Pinterest’s new mobile web experience is a Progressive Web App. In this post we’ll cover some of their work to load fast on mobile hardware by keeping JavaScript bundles lean and adopting Service Workers for network resilience.

Login to https://pinterest.com on your phone to experience their new mobile site

Login to https://pinterest.com on your phone to experience their new mobile site

Why a Progressive Web App (PWA)? Some history.

The Pinterest PWA started because they were focused on international growth, which led them to the mobile web.

After analyzing usage for unauthenticated mobile web users, they realized that their old, slow web experience only managed to convert 1% of users into sign-ups, logins or native app installs. The opportunity to improve this conversation rate was huge, leading them to an investment in the PWA.

Building and shipping a PWA in a quarter

Over 3 months, Pinterest rebuilt their mobile web experience using React, Redux and webpack. Their mobile web rewrite led to several positive improvements in core business metrics.

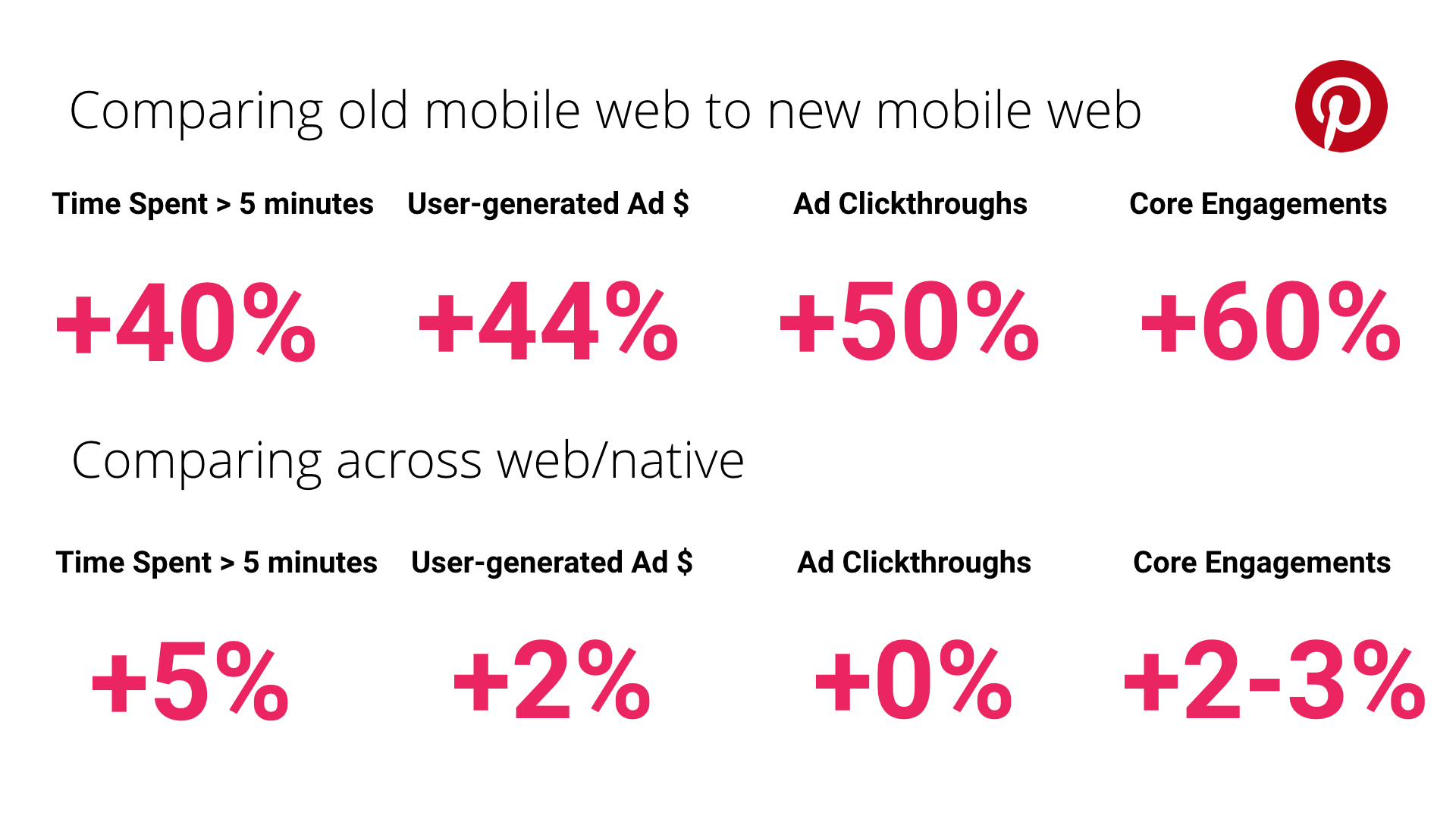

Time spent is up by 40% compared to the old mobile web experience, user-generated ad revenue is up 44% and core engagements are up 60%:

Their mobile web rewrite also led to several improvements in performance.

Loading fast on average mobile hardware over 3G

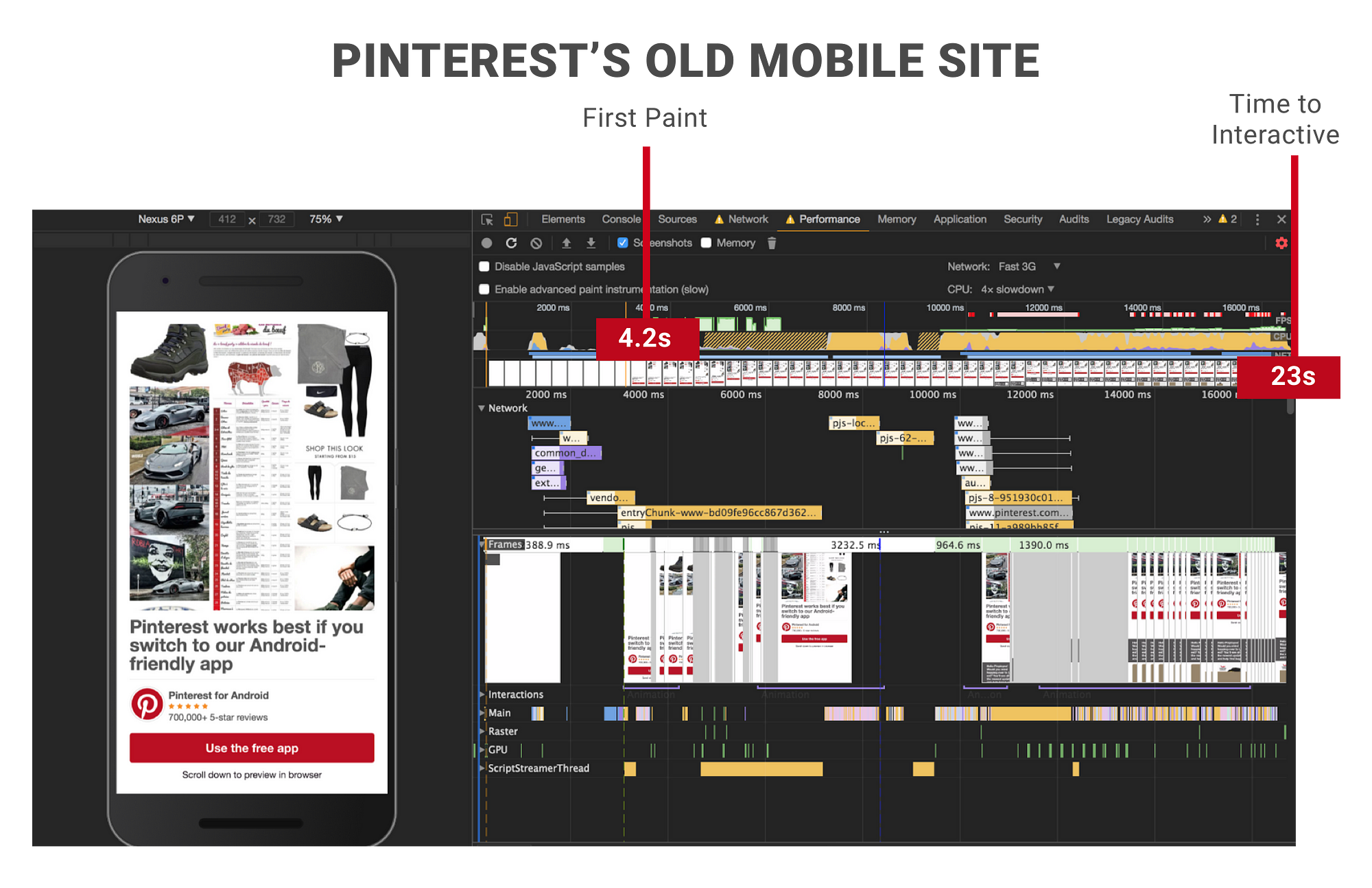

Pinterest’s old mobile web experience was a monolith — it included large bundles of CPU-heavy JavaScript that pushed out how quickly Pin pages could load and get interactive.

Users often had to wait 23 seconds before any UI was usable at all:

Pinterest’s old mobile web site took 23 seconds to get interactive. They would send down over 2.5MB of JavaScript (~1.5MB for the main bundle, 1MB lazily loaded in) taking multiple seconds to get parsed and compiled before the main thread finally settled down enough to be interactive.

Pinterest’s old mobile web site took 23 seconds to get interactive. They would send down over 2.5MB of JavaScript (~1.5MB for the main bundle, 1MB lazily loaded in) taking multiple seconds to get parsed and compiled before the main thread finally settled down enough to be interactive.

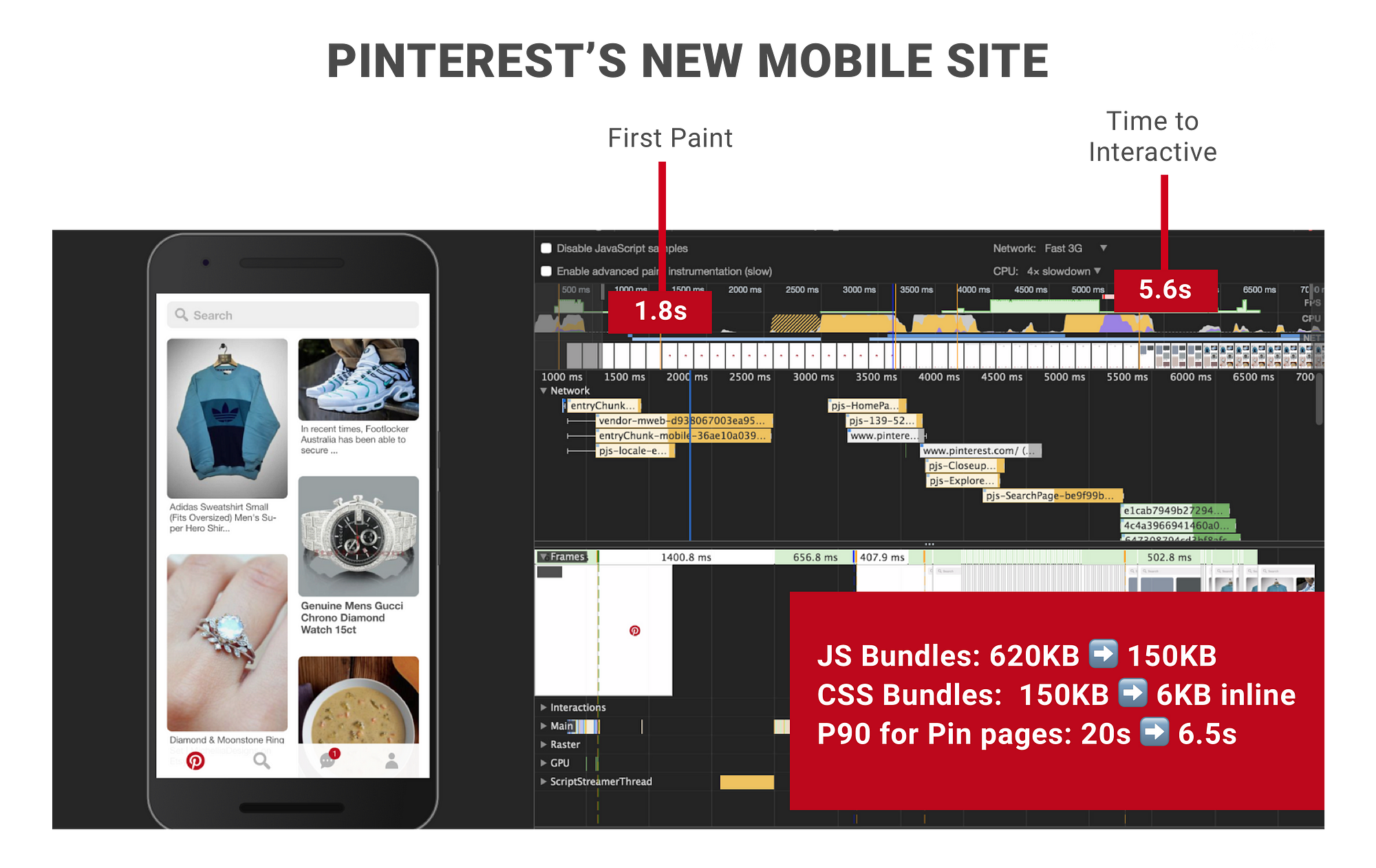

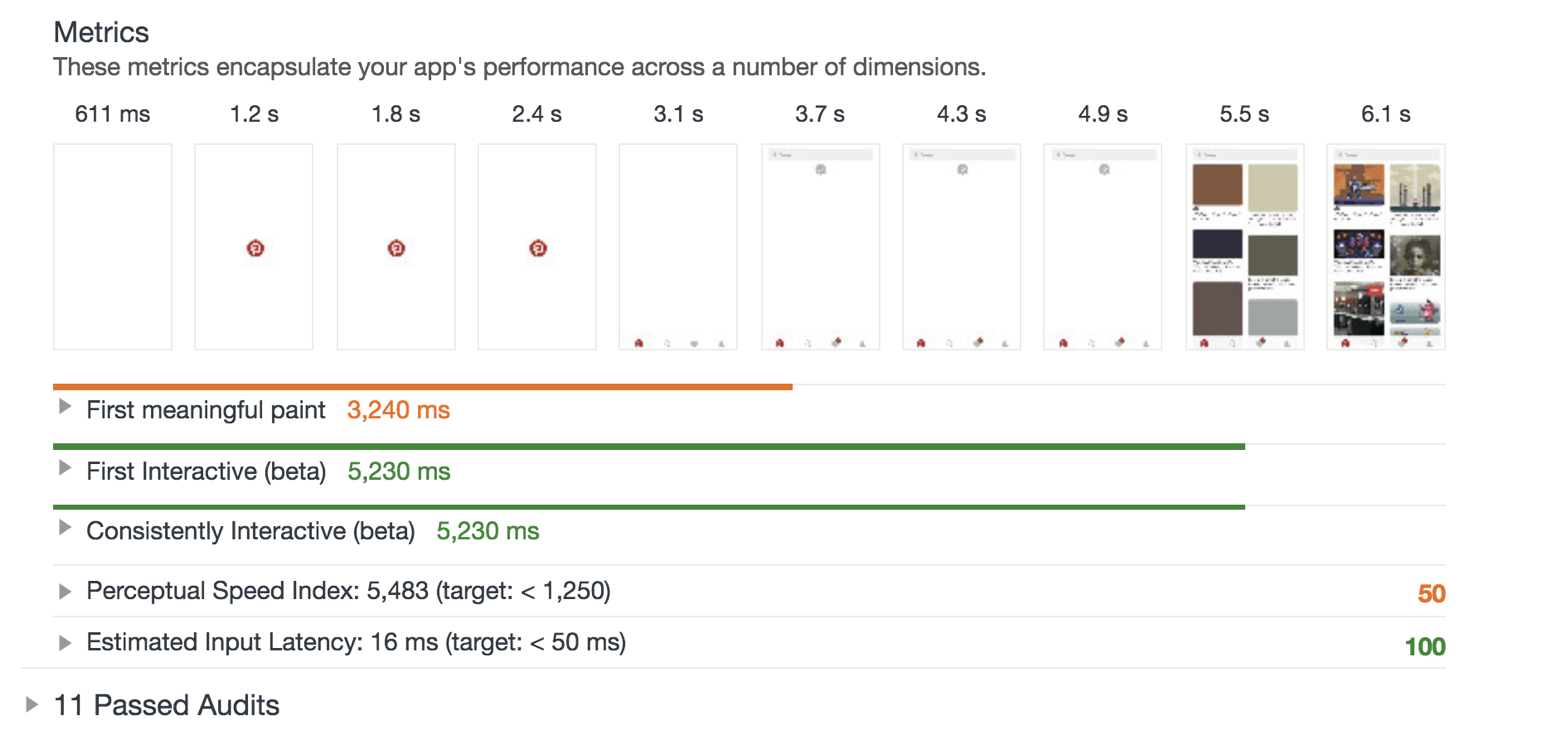

Their new mobile web experience is a drastic improvement.

Not only did they break-up & shave hundreds of KB off their JavaScript, taking down the size of their core bundle from 650KB to 150KB but they also improved on key performance metrics. First Meaningful Paint was down from 4.2s to 1.8s and Time To Interactive reduced from 23s to 5.6s.

This is on average Android hardware over a slow 3G network connection. On repeat visits, the situation was even better.

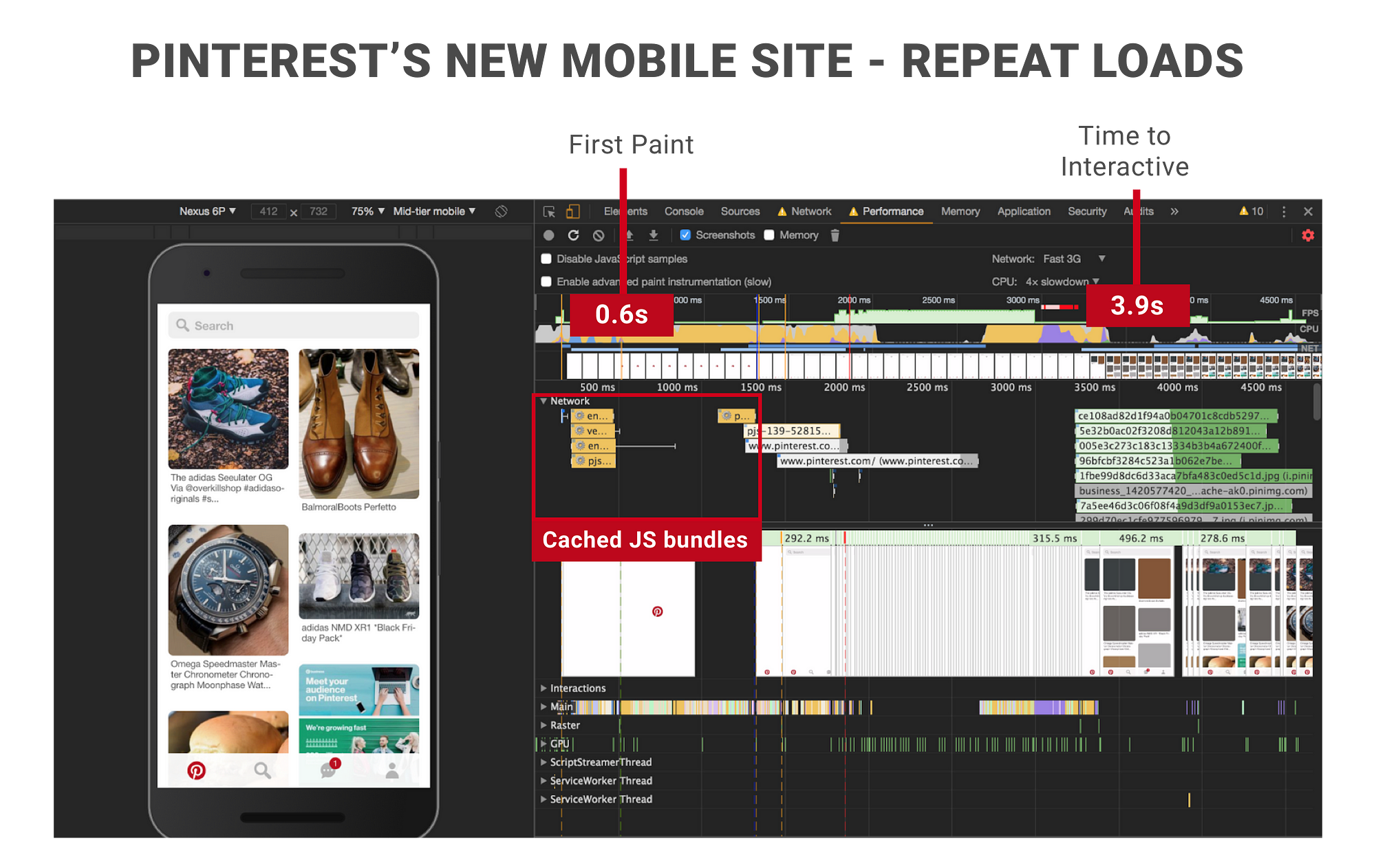

Thanks to Service Worker caching of their main JavaScript, CSS and static UI assets they were able to bring down time to interactive on repeat visits all the way down to 3.9s:

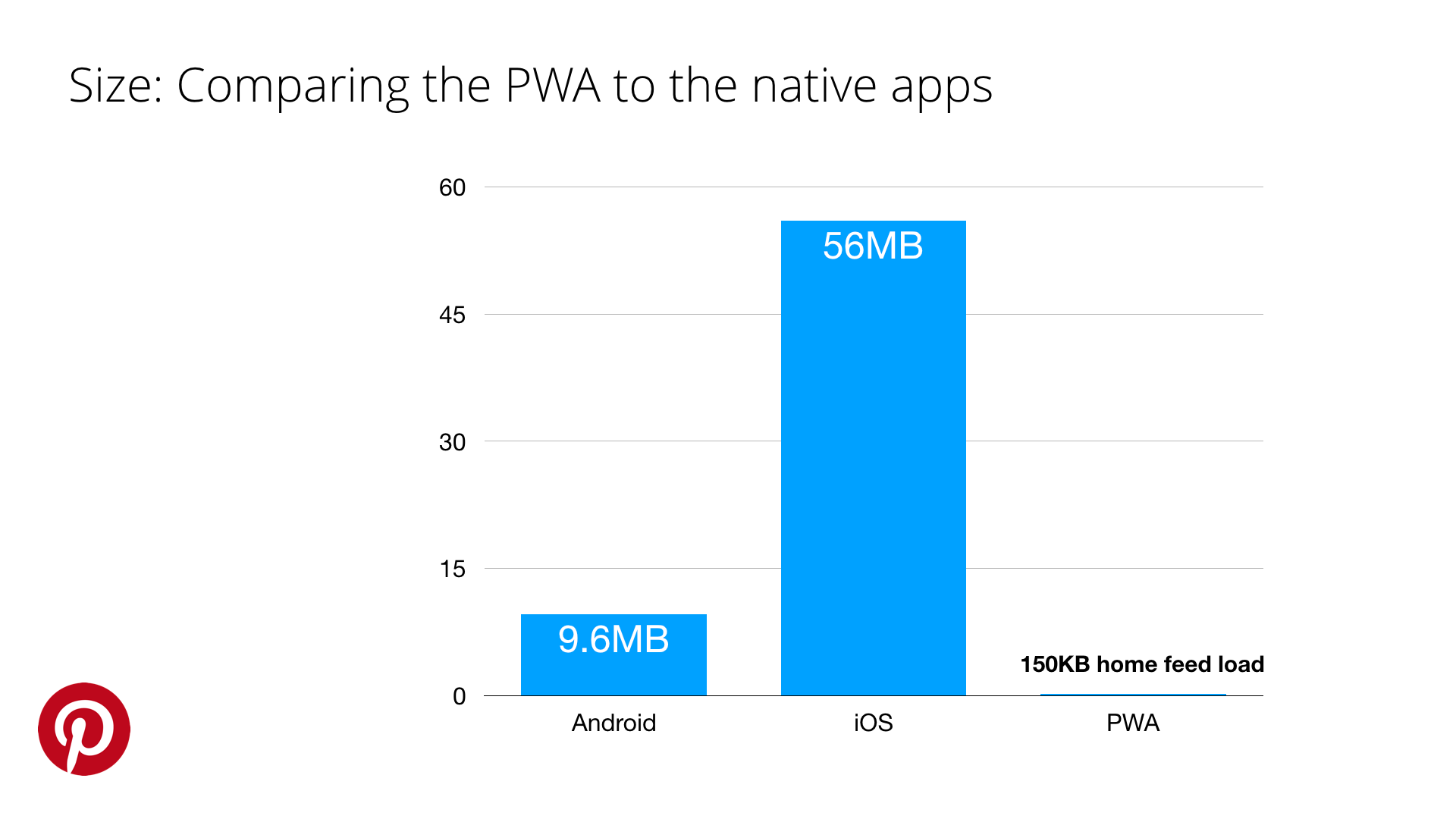

Although Pinterest vend iOS & Android apps, they were able to deliver the same core home feed experience these apps do on the web in a fraction of the upfront download cost — just ~150KB minified & gzipped. This contrasts with the 9.6MB required to deliver this experience for Android and 56MB for iOS:

It’s important to note that this isn’t comparing apples to apples, however. The PWA loads code for new routes on demand, and the cost of additional code is amortized over the lifetime of the application. Subsequent navigations still don’t cost as much data as the download of the app.

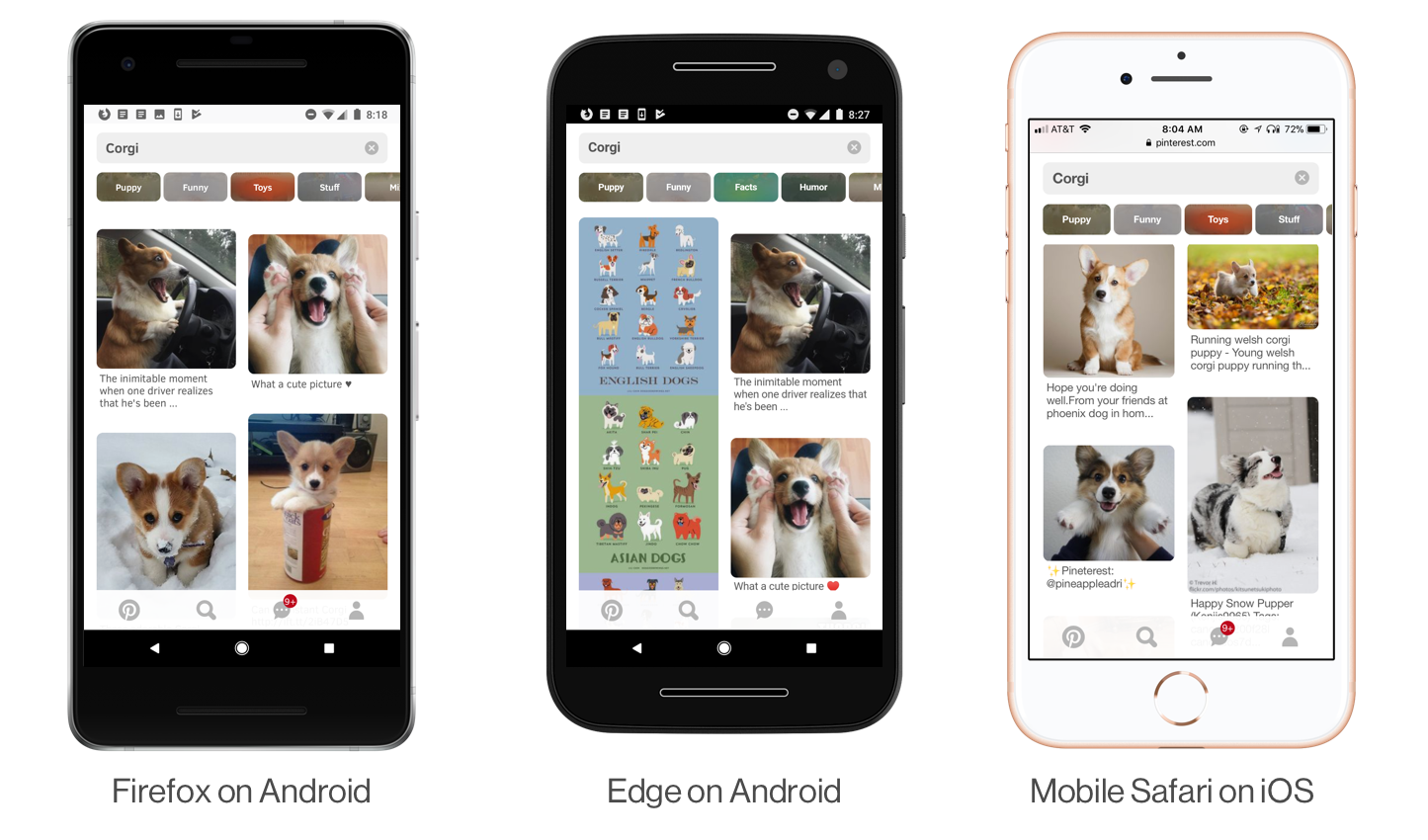

Pinterest’s Progressive Web App in Firefox, Edge and Safari on mobile.

Pinterest’s Progressive Web App in Firefox, Edge and Safari on mobile.

Route-based JavaScript chunking

Getting a web page to load and get interactive quickly benefits from only loading the code a user needs upfront. This reduces network transmission & JavaScript parse/compile times. Non-critical resources can then be lazily loaded as needed.

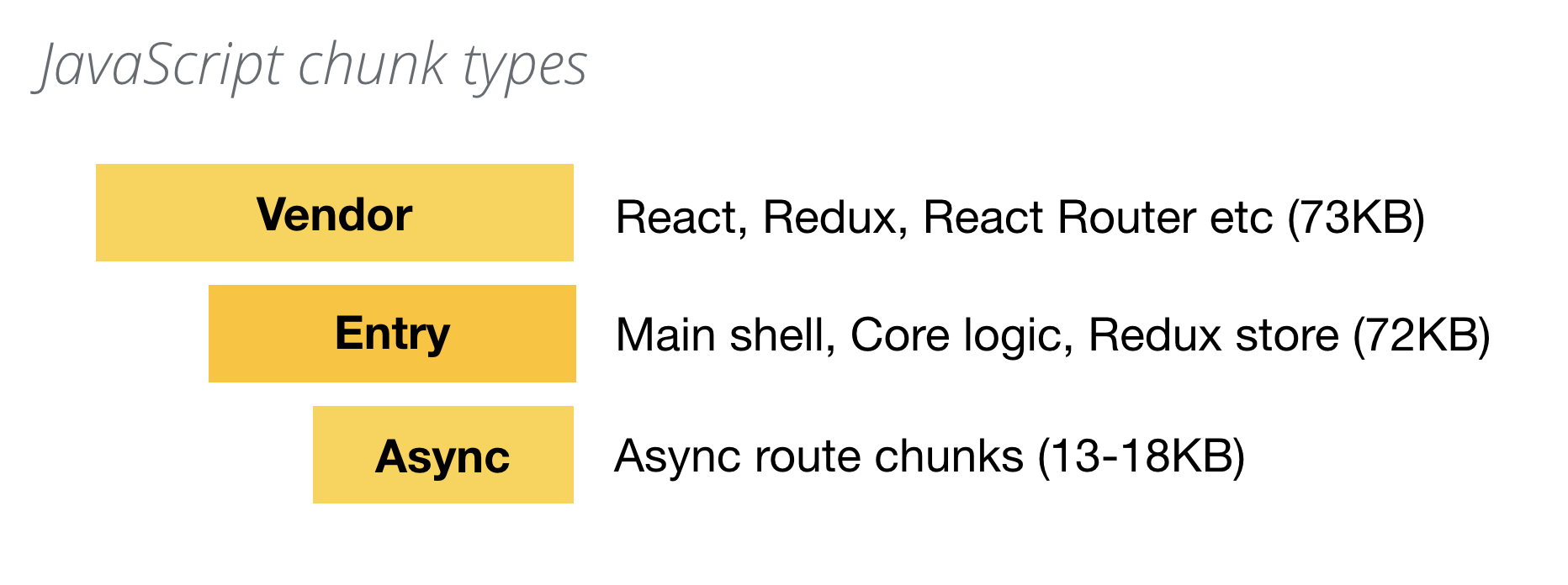

Pinterest started breaking up their multi-megabyte JavaScript bundles by splitting them into three different categories of webpack chunks that worked quite well:

- a vendor chunk which contained external dependencies (react, redux, react-router, etc) ~ 73KB

- an entry chunk which contained a majority of the code required to render the app (i.e. common libs, the main shell of the page, our redux store) ~ 72KB

- async route chunks which contained code pertaining to individual routes ~13–18KB

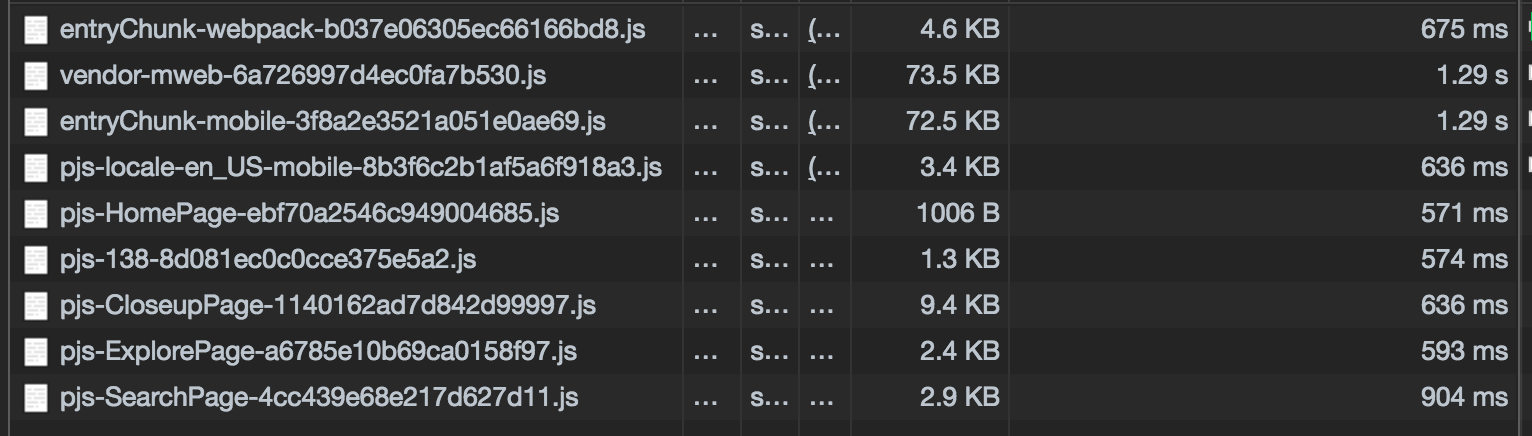

A Network waterfall for the experience highlights how a shift to progressively delivering code as needed avoids the need for monolithic bundles:

Pinterest uses webpack’s CommonsChunkPlugin to break out their vendor bundles into their own cacheable chunk:

They also used React Router for adding code-splitting to the experience:

Use babel-preset-env to only transpile what target browsers need

Pinterest use Babel’s babel-preset-env to only transpile ES2015+ features unsupported by the modern browsers they target. Pinterest targets the last two versions of modern browsers, and their .babelrc setup looks a little like:

There are further optimizations they can do to only conditionally serve polyfills as needed (e.g the Internationalization API for Safari) but this is planned for the future.

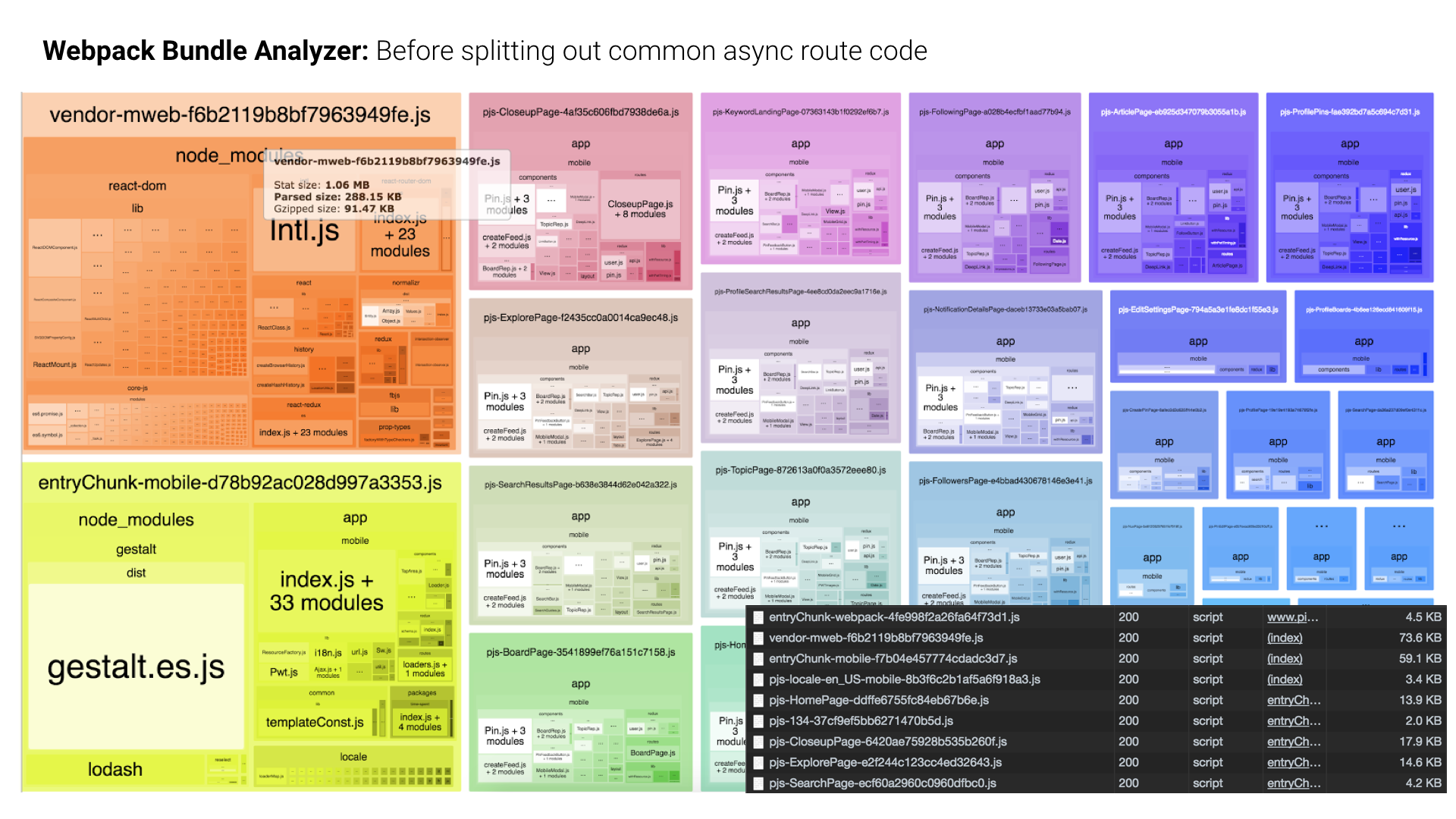

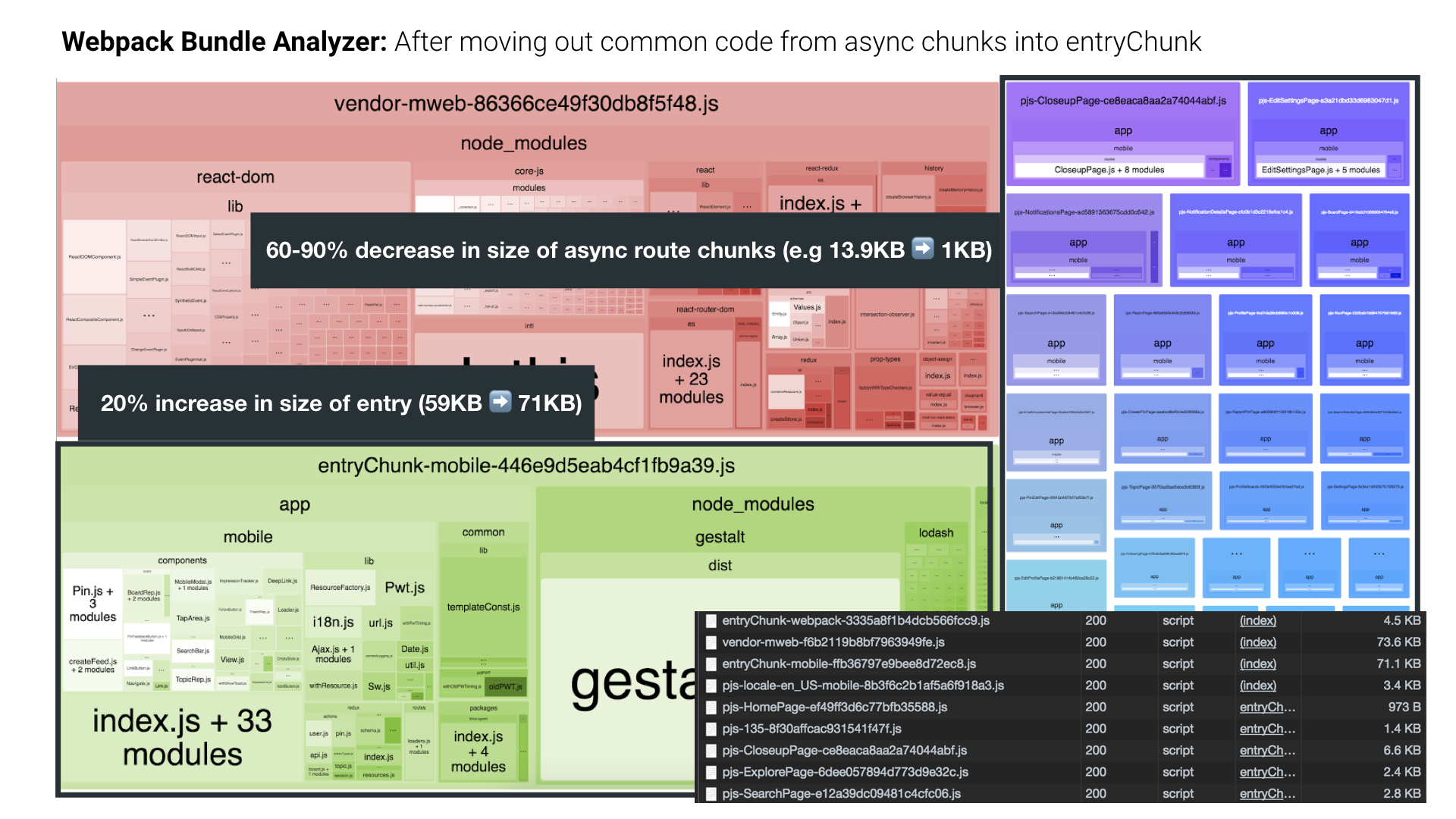

Analyzing room for improvement with Webpack Bundle Analyzer

Webpack Bundle Analyzer is an excellent tool for really understanding what dependencies you’re sending down to your users in JavaScript bundles.

Below, you’ll see a lot of purple, pink and blue blocks in its output for an earlier build of Pinterest. These are async chunks for routes being lazily loaded in. Webpack Bundle Analyzer allowed Pinterest to visualize that most of these chunks contained duplicate code:

Webpack Bundle Analyzer helped visualize the size ratio of this problem between all their chunks.

Using the information about duplicate code in chunks, Pinterest were able to make a call. They moved duplicate code in async chunks to their main chunk. It increased the size of the entry chunk by 20% but decreased the size of all lazily loaded chunks by up to 90%!

Image Optimization

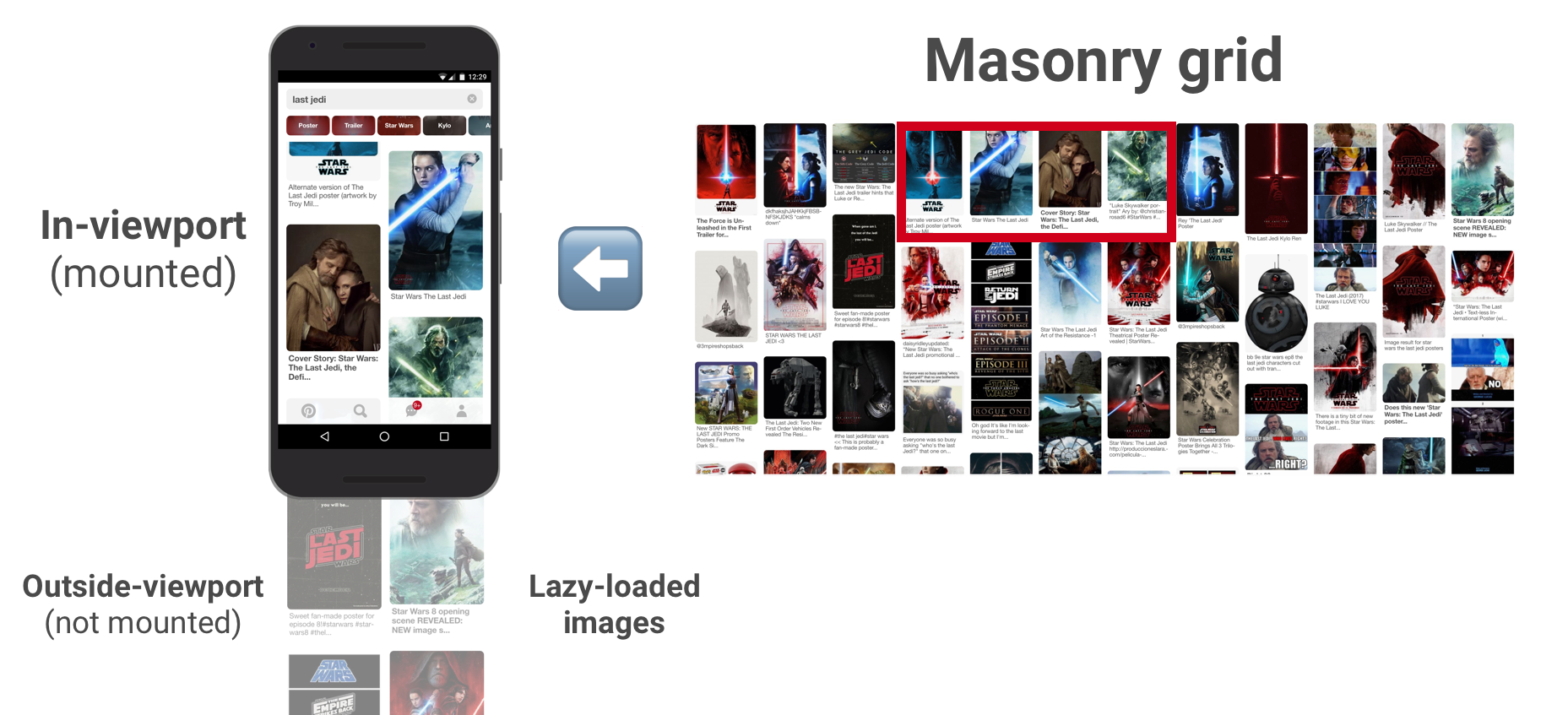

Most of the lazy-loading of content in the Pinterest PWA is handled by an infinite Masonry grid. It has built-in support for virtualization and only mounting children that are in the viewport.

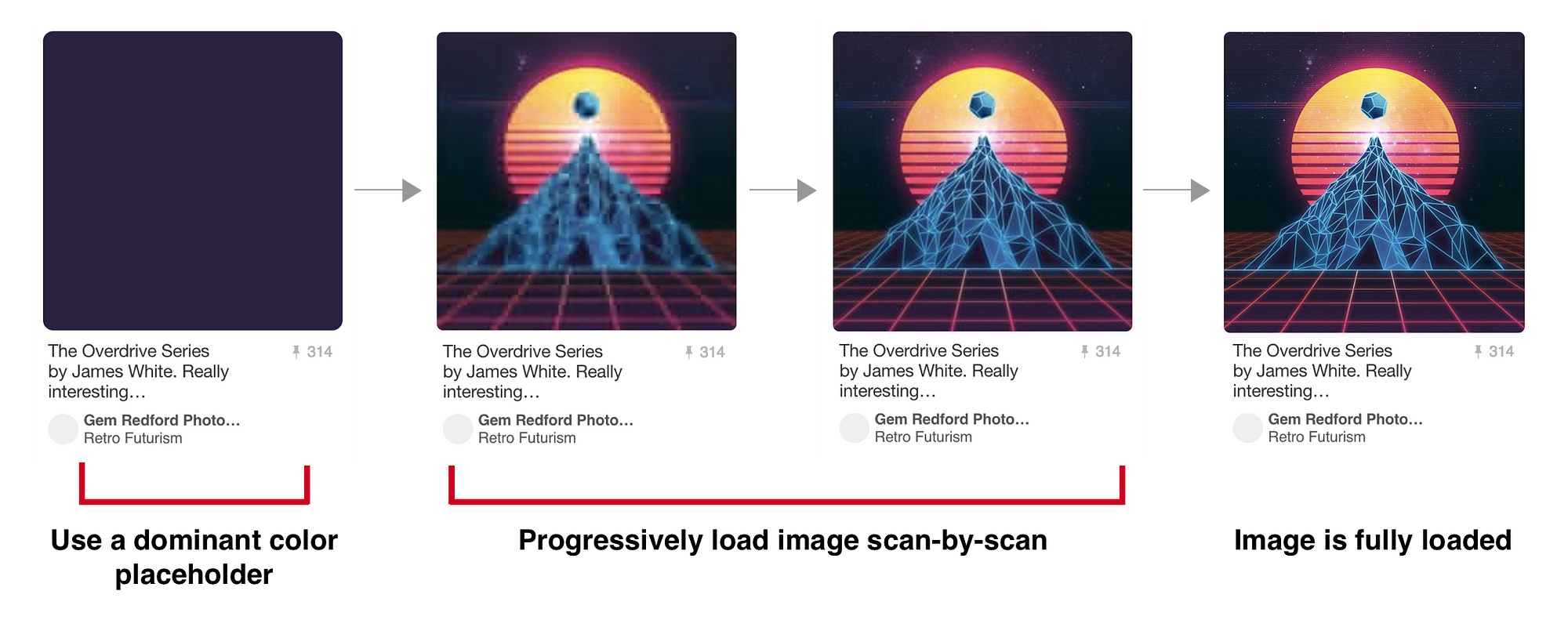

Pinterest also uses a progressive loading technique for images in their PWA. A placeholder with the dominant color is initially used for each Pin. Pin images are served as Progressive JPEGs, which improve image quality with each scan:

React performance pain-points

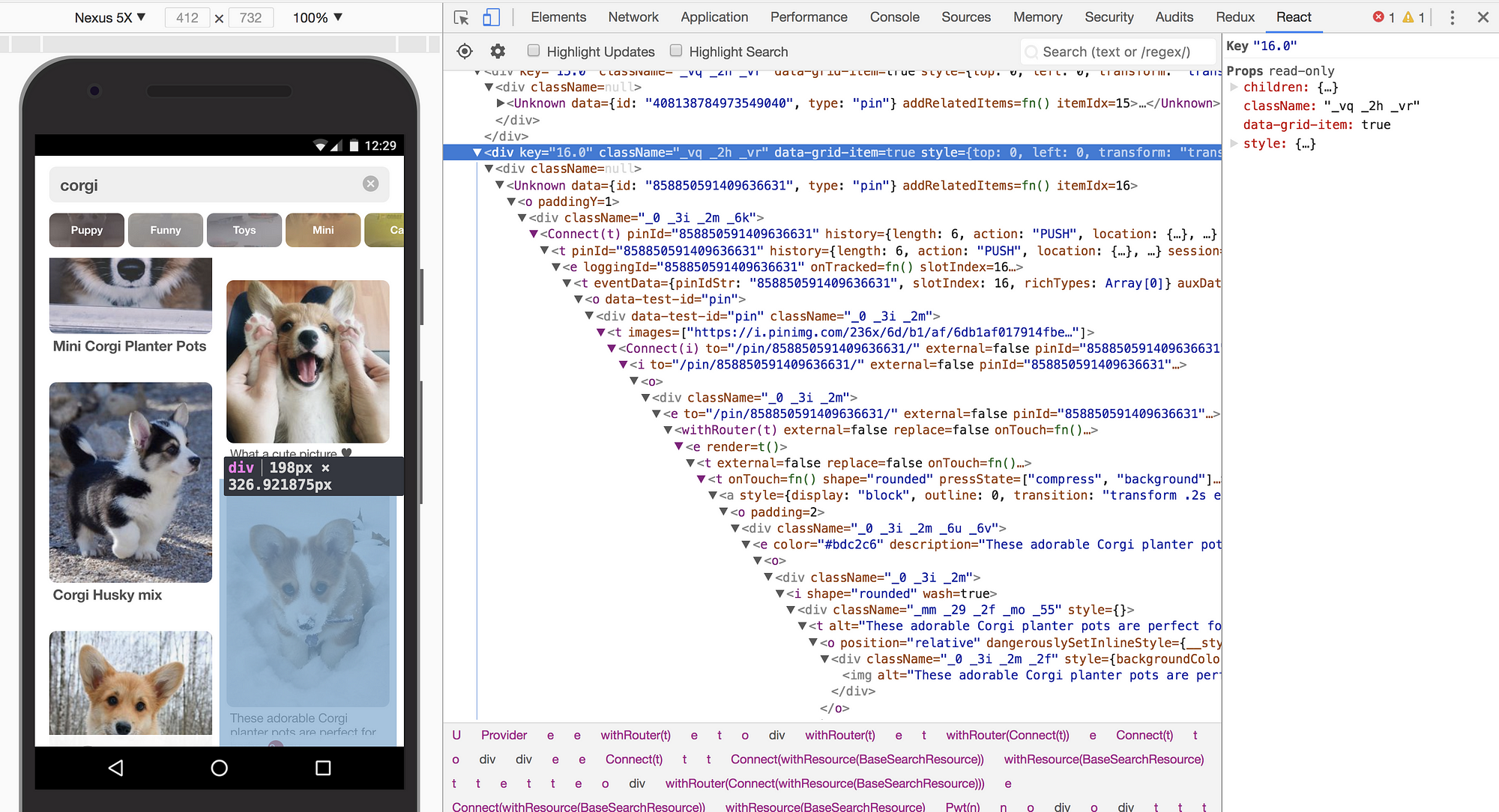

Pinterest ran into some rendering performance issues with React as part of their use of this Masonry grid. Mounting and unmounting large trees of components (like Pins) can be slow. There’s a lot that goes into a Pin:

Although at the time of writing Pinterest are using React 15.5.4, their hope is that React 16 (Fiber) will help a lot with reducing time spent unmounting. In the mean time, Virtualizing the grid helped significantly with component unmount time.

Pinterest also throttle insertion of Pins so that they can measure/render the first Pins quicker, but means there’s more overall work for the device’s CPU.

Navigation Transitions

To improve perceived performance, Pinterest also update the selected state of navigation bar icons independent of the route. This enables navigations from one route to another to not feel slow due to blocking on the network. The user gets visual UI painted quickly while we’re waiting for the data to arrive:

Experience using Redux

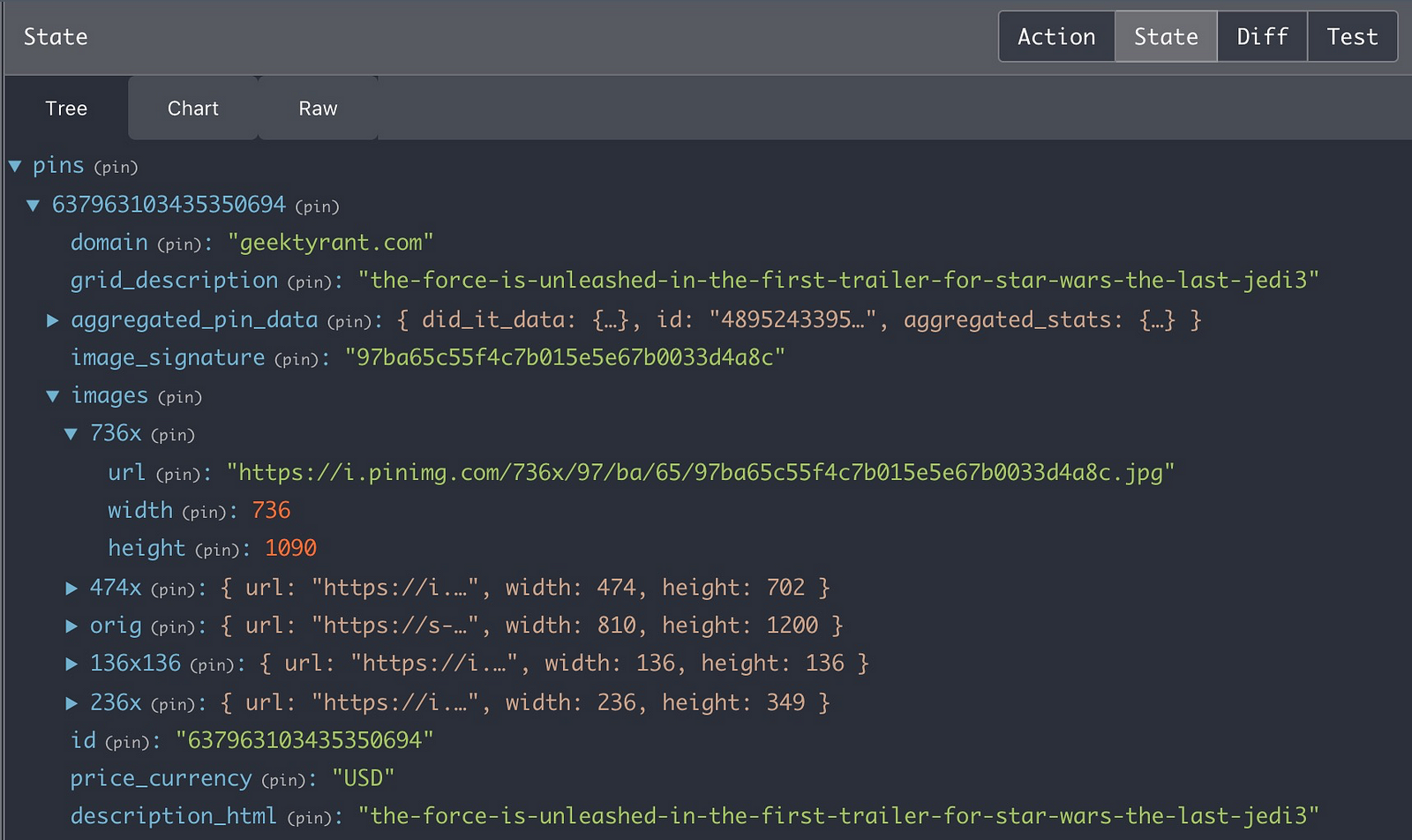

Pinterest use normalizr (which normalizes nested JSON according to a schema) for all of their API data. This is viewable from the Redux DevTools:

The downside to this process is that denormalization is slow so they ended up heavily relying on reselect’s selector pattern for memoizing denormalization during renders. They also always denormalize at the lowest level possible to ensure individual updates don’t cause large re-renders.

As an example, their grid item lists are just Pin IDs with the Pin component denormalizing itself. If there are changes to any given Pin, the full grid does not have to re-render. The trade-off is that there are a lot of Redux subscribers in the Pinterest PWA, though this hasn’t resulted in noticeable perf issues.

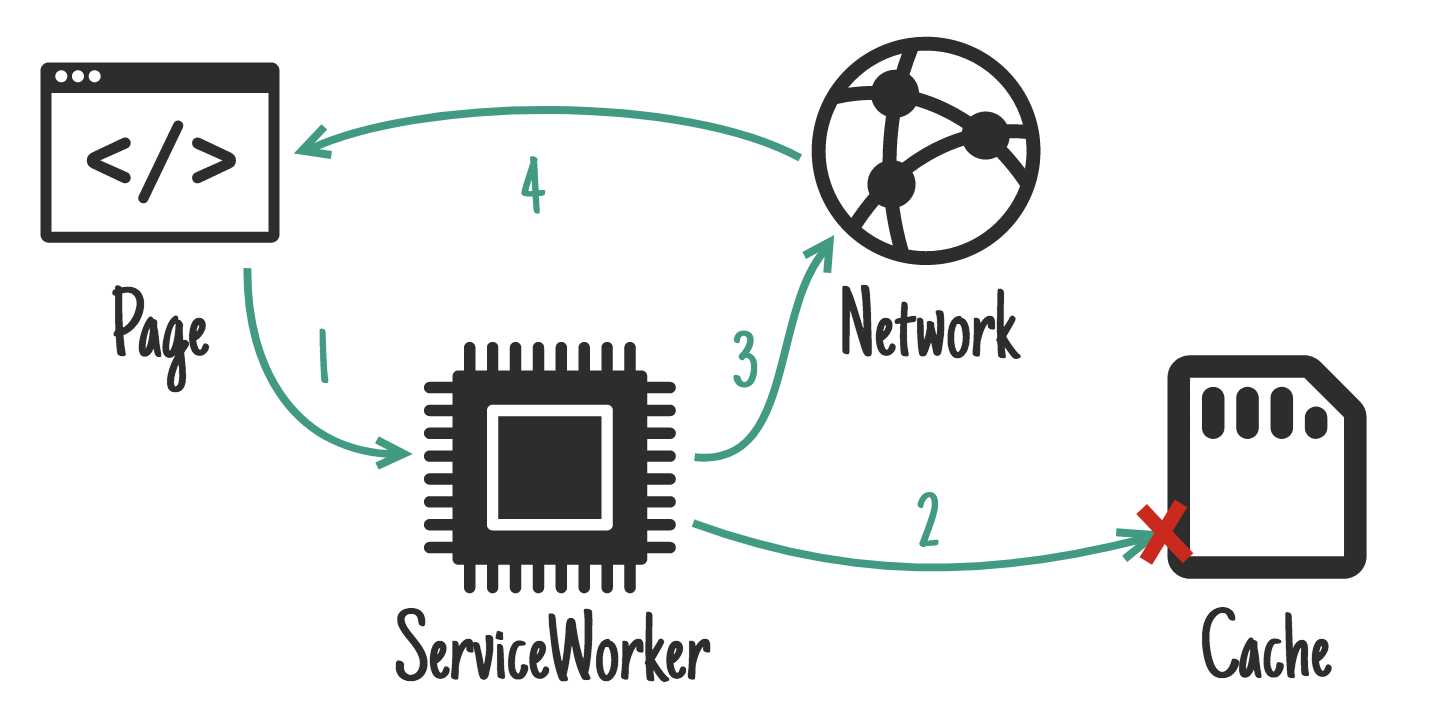

Caching assets with Service Workers

Pinterest use the Workbox libraries for generating and managing their Service Workers:

Today, Pinterest cache any JavaScript or CSS bundles using a cache-first strategy and also cache their user-interface (the application shell).

In a cache-first setup, if a request matches a cache entry, respond with that. Otherwise try to fetch the resource from the network. If the network request succeeds, update the cache. To learn more about caching strategies with Service Worker, read Jake Archibald’s Offline Cookbook.

In a cache-first setup, if a request matches a cache entry, respond with that. Otherwise try to fetch the resource from the network. If the network request succeeds, update the cache. To learn more about caching strategies with Service Worker, read Jake Archibald’s Offline Cookbook.

They define a precache for the initial bundles loaded by the application shell (webpack’s runtime, vendor and entryChunks) too.

As Pinterest is a site with a global presence, supporting multiple languages, they also generate a per-locale Service Worker configuration so they can precache locale bundles. Pinterest also use webpack’s named chunks to precache top-level async route bundles.

This work was rolled out in several smaller, iterative steps.

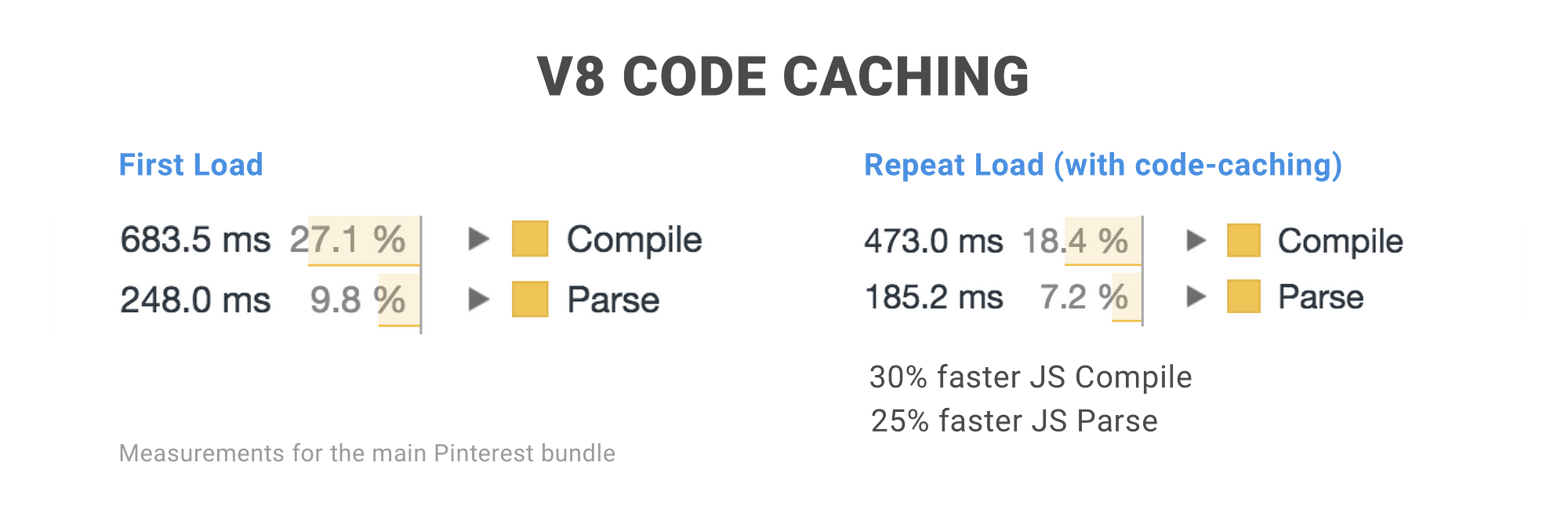

- 1st: Pinterest’s Service Worker only did runtime caching of scripts lazy-loaded on demand. This was to take advantage of V8’s code caching, helping skip some of the parse/compile cost on repeat views so they can load quicker. Scripts served from Cache Storage where a Service Worker is present can eagerly opt into code caching as there’s a good chance the browser knows the user will end up using these resources on repeat views.

- After this, Pinterest progressed to pre-caching their vendor and entry chunks.

- Next, Pinterest started precaching a few of the most used routes (like the home page, pin page, search page etc).

- Finally, they started generating a Service Worker for each locale so that they could also cache the locale bundle. This was important for not just repeat load performance, but also enabling basic offline rendering for most of their audience:

Application Shell challenges

Pinterest found implementing their application shell a little tricky. Because of desktop-era assumptions about how much data could be sent down over a cable connection, initial payloads were large containing a lot of non-critical info, like user’s experiment groups, user info, contextual information etc.

They had to ask themselves: “do we cache this stuff in the application shell? or take the perf hit of making a blocking network request before rendering anything to fetch it at all”.

They decided to cache it in the application shell, which required some management of when to invalidate the app shell (logout, user information updates from settings etc). Each request response has an appVersion — if the app version changes, they unregister the Service Worker, register the new one then on the next route change they do a full page reload.

Adding this information to the application shell is a little trickier, but worth avoiding the render blocking request for.

Auditing with Lighthouse

Pinterest used Lighthouse for one-off validations that their performance improvements were on the right track. It was useful for keeping an eye on metrics such as Time to Consistently Interactive.

Next year they hope to use Lighthouse as a regression mechanism to verify that page loads remain fast.

The Future

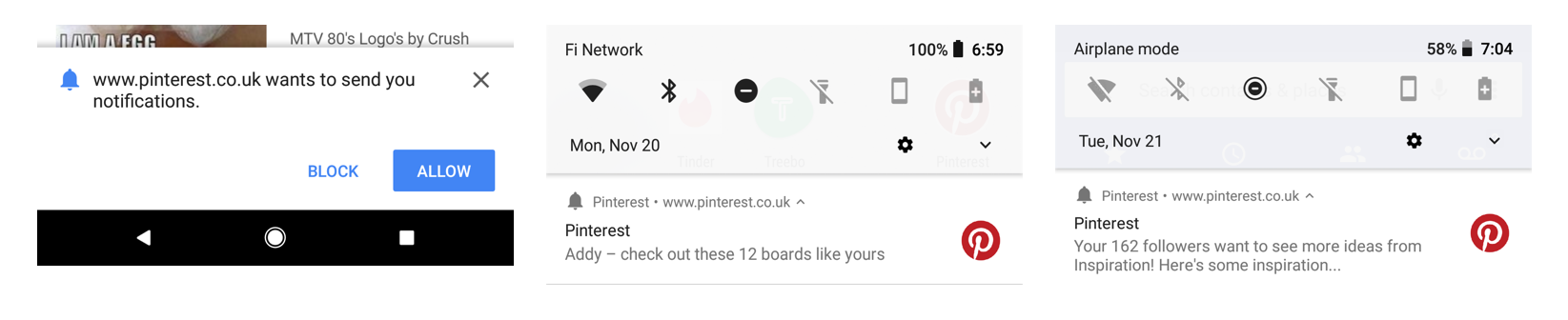

Pinterest just deployed support for Web Push notifications and have also been working on the unauthenticated (logged-out) experience for their PWA.

They are interested in exploring support for resource prioritization to preload critical bundles & reducing the amount of unused JavaScript delivered to users on first load. Stay tuned for more awesome perf work in the future!

Source: https://medium.com/dev-channel/a-pinterest-progressive-web-app-performance-case-study-3bd6ed2e6154